Cushner, K., McClelland, A., & Safford, P. (2006). Human diversity in education: An integrative approach. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Embracing multicultural education and supporting cultural pluralism in the classroom is all part of being culturally andlinguisticallyresponsive—recognizing the importance of and engaging others’ cultures and languages. The concept of a culturallyresponsive school encompasses how able each member of the school community is in interacting effectively with those from other cultures and what kind of school culture and climate are established by the staff as a whole. Consider how you might be culturallyresponsive in the following What Would You Do?

iVOOK/iStock/Thinkstock

Cultural proficiency journeys are complex, particularly when undertaken by an organization such as a school or district.

When a school achieves its full potential in being culturallyresponsive, it can be said that the school has achieved cultural proficiency. Indeed, Quezada, Lindsey, and Lindsey (2012) defined cultural proficiency as a process and described it as a journey that individuals and organizations take. It may also be perceived as a lens through which we can experience the world around us. Lindsey et al. (2014) noted that

the journey of Cultural Proficiency involves recognizing the beliefs that create mindsets. Beliefs that relate to race, ethnicity, gender, social class, religion or sexual orientation block effectiveness in cross-cultural communications and problem solving. It usually takes an awakening experience to challenge uninformed, negative, cultural beliefs and their underlying assumptions. (p. 12)

For an organization such as a school or district, the journey is a complex and multifaceted one that will take time and focused navigation. What do you envision the cultural proficiency journey looking like? Is it linear? Does it have detours, obstacles, barriers, or perhaps even dead ends? Why is the journey metaphor helpful?

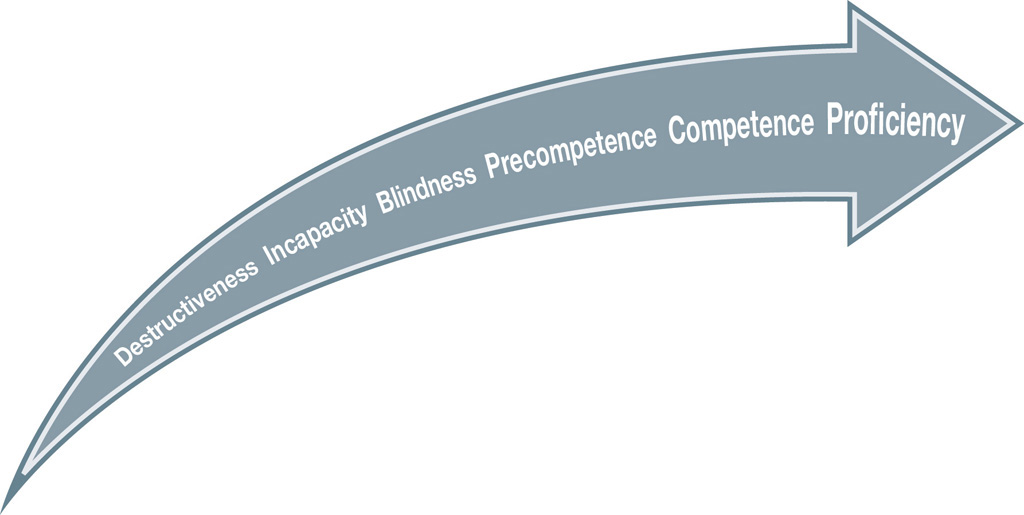

If you accept the journey metaphor, it can be visualized as a passage through a six-point continuum (see Figure 2.2). The first three stages emerge as a result of barriers to understanding and the inability or lack of adequacy to respond to other cultures. The focus is on viewing diversity as a problem or a challenge (Lindsey & Daly, 2012), whereas the last three stages develop as a result of focusing on our own practice as educators, as we examine our beliefs and actions and strive to reach equity. The six stages are described in the following paragraphs.

Cultural destructiveness refers to the practice of not merely ignoring but intentionally negating or eliminating differences. Imagine a school with a “no hat policy” that does not allow any hats indoors during school hours. If the policy remains in effect even after students for whom head coverings are a religious requirement arrive in the community, an important aspect of those students’ culture is negated. If the school insists that no exceptions can be made, this rule leads to the denial of other people’s cultures in the school. Or think of teachers who insist that they are “not good at languages”; they cannot pronounce the names of their newly arrived immigrant children, so they just give “American” names to their students. No consideration is given to what erasing one’s name means for the child: Replacing the name given by the immediate cultural group (family or extended family) is like eliminating a dimension of that child’s identity.

James Banks (2012) described six stages of cultural proficiency. These stages may be nonlinear for some individuals.

Illustration by Steve Zmina

Cultural incapacity refers topractices that recognize that cultural differences exist, but minimize and even trivialize them, or make them appear to be wrong and unacceptable. Within the context of education, imagine a school where some students are requesting to be allowed time for praying once or twice a day, but the policy in place claims that praying is a religious practice that must be separated from school and needs to be taken outside of the building and school hours. Or consider another, much more common scenario: giving weekly quizzes or end-of-unit tests that carry even more weight and prove to be rather stressful for all learners, but forbidding teachers from giving extended time to their English learners to finish the test. How frustrating is it when dictionaries are not made available to ELLs, even though processing information takes longer when completing a task in a new language? Another example of cultural incapacity is when teachers design tests with references to American culture that ELLs may not understand. For instance, a math test contains word problems about types of transportation more commonly found in the United States (such as subway systems or elevated trains); students are not able to do well on this type of test, not because they do not understand the math or other concepts, but because they do not understand the references to American culture. Thesepractices ultimately disempower the students who see themselves as the ones in the wrong.

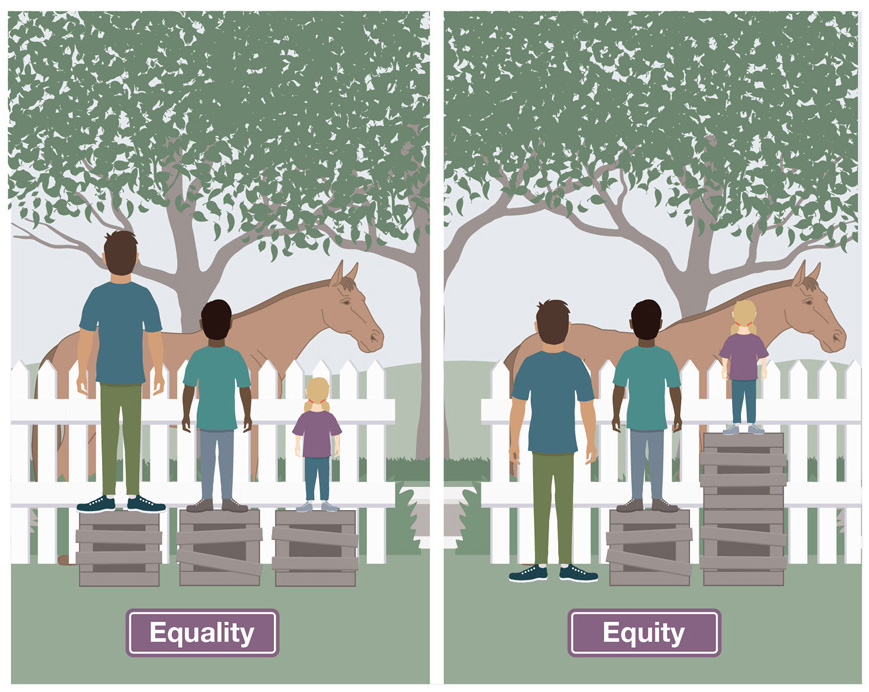

Cultural blindness can best be understood as a choice: pretending not to see or acknowledge other cultures—especially marginalized groups—and ignoring what lived experiences and complex realities such groups have within the school or the larger community. Note that this text intentionally uses the term equity rather than equality. When teachers refer to equality, they are most likely speaking about opportunities that grant students equal status, rights, or experiences within the school. On the other hand, the term equity relates to treating students fairly in schools. Consider Figure 2.3. In the left panel of the illustration, the children are each being offered a step to better see the horse. However, the smallest child still cannot see the horse. The step solution does not take into account the difference in height: Though the children are given equal access to the same step, their individual results are not equitable. Compare this to the right panel of the illustration, in which different-sized steps are specifically chosen so that each child can have an equitable view of the horse.

Equality and equity are not the same, and distinguishing issues of equality versus equity requires thoughtful consideration from educators.

Illustration by Steve Zmina

When the words equity and equality are confused, it often coincides with cultural blindness. Educators might claim that they treat everyone equally in the name of accepting diversity, when in fact equitable treatment is what is needed. Imagine the teacher who proudly claims she sees no color: The students she teaches could be of any race or ethnicity; it does not matter to her. In this example, the teacher is demonstrating equality in her viewpoint, but not equity in her actions. Although they might be perceived as well intentioned, educators who embrace this approach of declaring cultural blindness dismiss the cultural differences that do exist and often define the child’s identity.

Cultural precompetence signifies a critical stop on this journey to cultural competence where individuals and educational organizations recognize that differences among cultures do exist and make a sincere effort to respond to such differences, but do so inadequately. There is increasing shared awareness that there is so much more to learn about the marginalized groups in the school community and how to best interact with them and include them. There is also an emerging desire to get to know those who are different, so schools might create cultural fairs or multicultural days and celebrations, in which families are invited to bring a traditional meal, share some cultural artifacts, or wear traditional outfits. The teachers who replaced the child’s hard-to-pronounce name at an earlier stage would now ask the child to say the name slowly and explain what the name means in the native language.

Cultural competence indicates that the individuals and school community see and understand the cultural differences that exist and are able and willing to continuously expand their understanding of all cultures. Both personal values and behaviors and the school’s policies andpractices become inclusive of the cultures that may be new to the community or different from the majority in the school. Consider the school that opens its doors to the community and allows a local organization to establish a Saturday program to teach the native language and culture of the children. “By being culturally competent, schools reinforce students’ identities and create a sense of academic and physical safety for students and their families” (Tung et al., 2011, p. 9).

Cultural proficiency indicates not just a heightened awareness of diversity andresponsive actions to the many cultures in the community, but also a commitment to advocacy and lifelong learning about equity. Schools that have arrived at the cultural proficiency level have a strong vision about their purpose: to create a socially just society through education. They will clearly articulate this vision and enact it in their daily practice.

Nisian Hughes/Stone/Getty Images

All students are engaged in the lesson with culturally andlinguisticallyresponsive instructional strategies fostered by effective planning.

A complete instructional cycle consists of preparing a lesson plan, delivering instruction, assessing whether the students have met the learning targets (i.e., grasped the purpose of the lesson), and then reflecting on the process and outcomes of thisteaching–learning cycle. The challenge that teachers of English learners face is to ensure that the entire instructional cycle reflects culturally andlinguisticallyresponsivepractices. During lesson preparation, keep in mind that it is the students you areteaching and not just the content and language. In Chapter 8, you will learn more about how to plan instruction with learner diversity and needs in mind. In Chapters 8 and 9, you will learn to apply culturally andlinguisticallyresponsive instructional strategies as well as to develop an understanding of formative and summative assessmentpractices that are aligned to current research and the needs of ELLs. This chapter, however, offers—as a preview—a brief overview of key ideas to keep in mind for planning, lesson delivery, and assessment. These ideas can be organized into two main categories (Giouroukakis & Honigsfeld, 2010): culturallyresponsiveteachingpractices andlinguisticallyresponsiveteachingpractices.

As schools strive to achieve cultural proficiency, they are often noted as being proactive, and teachers in those schools are admired for demonstrating culturallyresponsiveteaching (CRT) (Gay, 2010). Culturallyresponsiveteaching (CRT)refers to a pedagogy that engages and responds to all learners and respects their individual cultures and backgrounds while offering equitable access to education. Teachers who engage in culturallyresponsiveteachingpractices

Working in tandem with culturallyresponsiveteachingpractices,linguisticallyresponsiveteachingpractices foster opportunities for students to use their multiple languages effectively and to learn to communicate in a variety of contexts. Teachers who engage inlinguisticallyresponsivepractices

Delivering a high-quality product at a reasonable price is not enough anymore.

That’s why we have developed 5 beneficial guarantees that will make your experience with our service enjoyable, easy, and safe.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more